Provincial Funding: What School Boards Rely Upon to Maintain School Infrastructure

Sadly, in the Fall Economic Statement from the Ford government this past week, we learned that base funding for education was being cut by $460-million. Minister Lecce defended his government’s actions, stating that “if you account for everything all other ministries are spending to help schools, the kids and teachers are still ahead.”

Ontario education minister defends $460 million base education funding cut to schools, says spending across government more than makes up for ithttps://t.co/6625qyz8np pic.twitter.com/7wHfsXArY7

— CP24 (@CP24) November 5, 2021

Perhaps this provincial funding cut is a matter of reporting. Perhaps not. The Ford government seems to intentionally create confusion when it releases numbers and data, and it consistently avoids transparency. Therefore, comparing year over year numbers and data is increasingly challenging, if not downright impossible. Thus, Fix Our Schools is not overly interested in debating the minutiae of this cut to education funding. We are, however, extremely interested in rebutting Minister Lecce’s statement and belief that “if you account for everything all other ministries are spending to help schools, the kids and teachers are still ahead”.

Perhaps this provincial funding cut is a matter of reporting. Perhaps not. The Ford government seems to intentionally create confusion when it releases numbers and data, and it consistently avoids transparency. Therefore, comparing year over year numbers and data is increasingly challenging, if not downright impossible. Thus, Fix Our Schools is not overly interested in debating the minutiae of this cut to education funding. We are, however, extremely interested in rebutting Minister Lecce’s statement and belief that “if you account for everything all other ministries are spending to help schools, the kids and teachers are still ahead”.

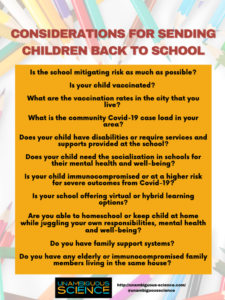

We believe that if the Ford government were to actually engage with education stakeholders, they would learn that the kids and teachers are absolutely not “ahead” by any measure these days. In fact, should our provincial government pursue authentic engagement with its stakeholders, they may even hear that this flippant and vague explanation of a cut to education funding is offensive, and that Ontario students, teachers, and education workers are struggling to catch up from the ongoing pandemic challenges. In the lead-up to a provincial election, Minister Lecce’s disregard and casual dismissal of the real needs of public schools and education is frustrating and, indeed, disturbing.

Fix Our Schools also believes that a complete rethink of provincial funding for schools and education is imperative, and that any new funding approach to school infrastructure must begin with a commitment to providing the funding actually needed to achieve the goals and outcomes we envision for school infrastructure. Additionally, any responsible funding model would also include:

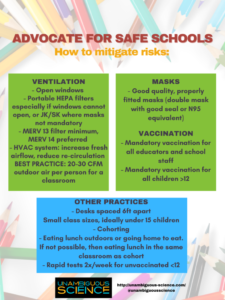

- Standards of good repair that include not only the outstanding repairs currently collected, but also items such as: portables; ventilation and indoor air quality; drinking water quality; asbestos remediation; accessibility; schoolyards, classroom temperatures; and cleanliness.

- Metrics that must be collected at given time intervals and compared against the set standards in order to confirm that investments and funding provided are achieving the desired outcomes

Standards & Metrics: During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Moving Forward

Without a set of standards in place for school infrastructure, no metrics are being collected and assessed to confirm that desired outcomes are being achieved. Without a set of standards there is no way to determine if an adequate level of funding is being provided to reasonably be able to achieve these outcomes. In the long-term, we know that school conditions matter. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, good school conditions can reduce absenteeism, improve test scores, and improve teacher retention. It is clear that in the long-term, Ontario absolutely needs a comprehensive set of standards for school infrastructure; and metrics in place to ensure those standards are being met and properly funded. Is this the government to do that?

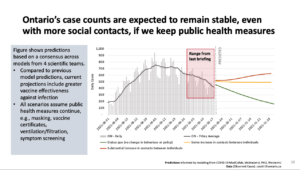

In the short-term, as we move through this tenuous time towards the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, let’s consider standards and metrics as they relate to ventilation and indoor air quality (IAQ). Ontario’s science table believes that provincial case counts will remain stable, even as social contacts increase, so long as public health measures such as masking, vaccine certificates, ventilation/filtration and symptom screening remain in place.

In the short-term, as we move through this tenuous time towards the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, let’s consider standards and metrics as they relate to ventilation and indoor air quality (IAQ). Ontario’s science table believes that provincial case counts will remain stable, even as social contacts increase, so long as public health measures such as masking, vaccine certificates, ventilation/filtration and symptom screening remain in place.

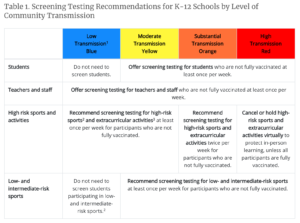

While the Ford government has provided funding for school boards to “improve ventilation”, they have not instituted any standards for what IAQ is required to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to improve health outcomes for students, teachers, and education workers during this pandemic. Furthermore, the Ford government has not provided any direction or funding to school boards to collect metrics on ventilation and IAQ, so we have no sense of whether the investments that school boards have made in ventilation improvements have yielded desired outcomes. This is simply fiscally irresponsible.

#Ventilation & #Filtration

Set the target. 🎯

Do the measurements and the math, and get to it!

Siegel @IAQinGWN notes the noise issue of portable filters, @WBahnfleth suggests air changes between class rotation. #MBed #Onted https://t.co/JxIT4SYhZ0— David Elfstrom (@DavidElfstrom) September 22, 2021

In the short-term, standards, metrics and ongoing funding are urgently needed for ventilation and indoor air quality in Ontario’s schools. And, in the longer-term, standards for all facets of school infrastructure, metrics to assess these standards, and adequate, stable provincial funding to ensure meeting these standards is possible are all absolute imperatives for Ontario’s schools.