Before the COVID-19 pandemic took centre stage in our lives, lead in drinking water had been in the headlines. A 2019 Toronto Star article entitled, “We can do better. Province concedes it must be more transparent about lead in school water“, featured a massive investigation revealing over 2,400 schools and daycares in Ontario with exceedances of lead in drinking water over the previous two years. At that time, the provincial government had acknowledged it could “do better”.

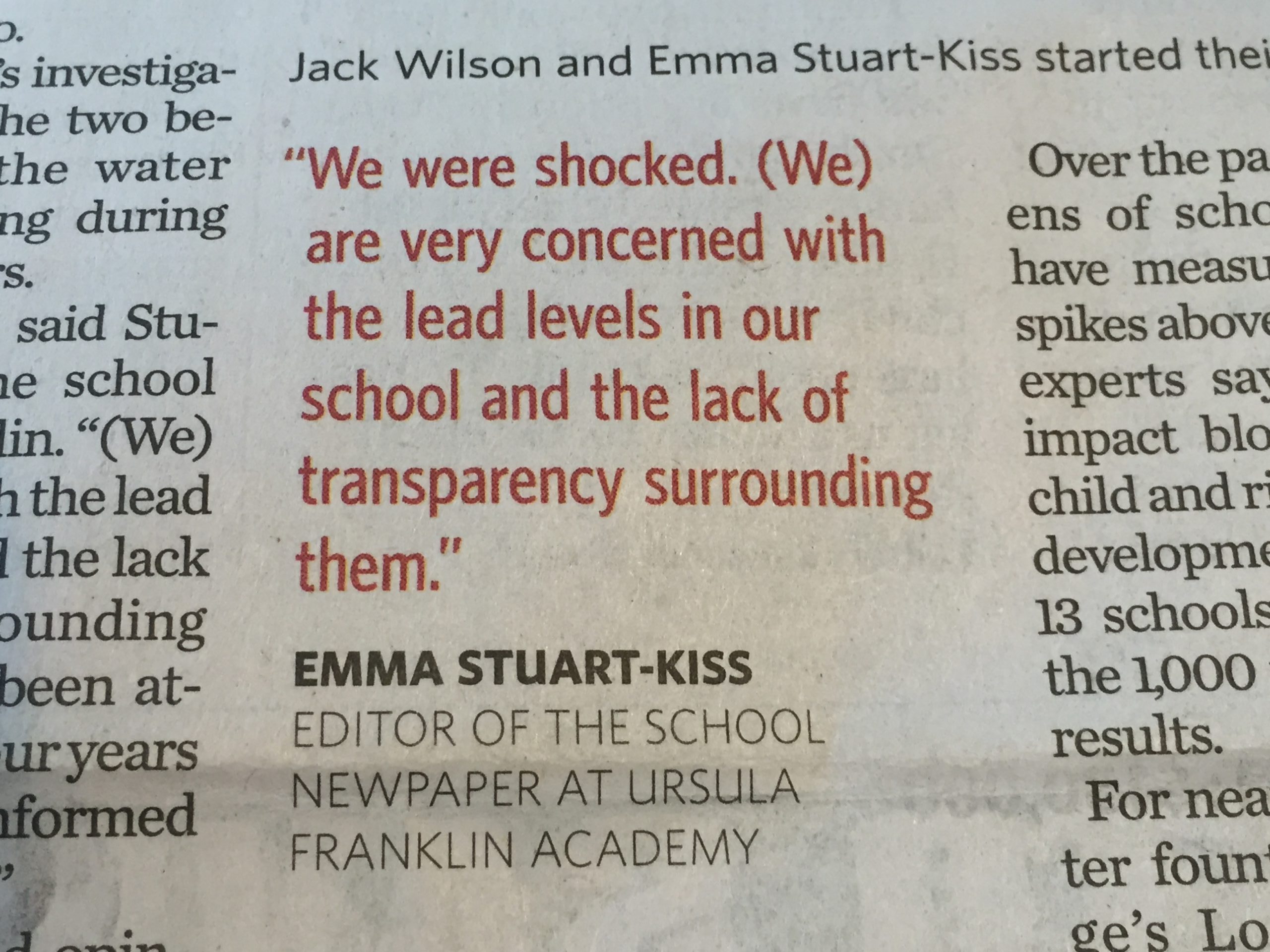

Almost two years later, an investigative piece published on June 11, 2021 in the Toronto Star revealed that “a third of Ontario schools still have dangerous levels of lead in drinking water – two years after Province pledged to fix it.” According to this recent data, one in 10 water tests from Ontario schools and daycares showed levels of lead above Health Canada’s maximum accepted concentration of five parts per billion (ppb). Schools and daycares are not required to tell parents and students when lead exceedances are found.

Lead can have many negative impacts, including lowering IQ and triggering behavioural disorders. According to a March 2021 study published in the Annals of Epidemiology, students in Ontario schools with lead exceedances between 2008 and 2016 scored lower in reading, writing and math testing, compared with students in schools without lead exceedances.

If high lead levels are found in a school’s water supply, as per provincial guidelines, school staff must flush the pipes by opening the tap and letting cold water flow for at least five minutes, or in some instances install a filter, and in other cases decommission the tap for use. Routine flushing of pipes is the most common solution, and many experts, such as Bruce Lanphear, a leading Canadian water researcher at Simon Fraser University, view flushing as only a short-term fix that does not prioritize the health of students. Lanphear suggests that what is actually needed is to eliminate taps or fountains with lead contamination. However, removing lead pipes that wind their way through building walls and floors is expensive. Given that Ontario’s schools rely upon provincial funding for repair and renewal of schools, and given that Ontario’s schools currently have a $16.3-billion repair backlog, it is difficult to imagine school boards having the means to properly address lead in school drinking water without additional provincial support – in the form of both funding and policies.

When parents send their children to school or daycare, they presume that the drinking water available to them is safe and free from any lead. Clearly, this is still not the case – even though this issue was clearly identified back in 2019. We’d suggest the same changes we recommended years ago are urgently needed today:

The Province must institute a policy mandating all school boards to report lead exceedances to parents and students. As one school principal said in this Global News report, “a clear ministry policy would help guide schools in what they should be communicating to parents and students”. Fix Our Schools believes that transparency about the state of our children’s schools is extremely important. While certain school boards, such as the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), have committed to being transparent by routinely publishing and updating disrepair data, and by starting to publish drinking water results, this is not the norm. Therefore, we urge the provincial government to institute a clear communication policy on drinking water safety in schools and daycares to ensure full transparency. In the spirit of transparency, we’ve also been routinely calling on the provincial government to update and release its disrepair data for all of Ontario’s publicly funded schools.

The Province must provide adequate funding that is designated specifically to addressing lead in drinking water. There is currently no provincial funding provided to school boards (or municipalities) to specifically address lead in drinking water. Given that most school boards face many urgent repairs every day such as leaking roofs, unless funding is provided to address lead in drinking water, the solution in many instances where exceedances are found may just be to cap off drinking water sources and place “handwashing only” signs on sinks in classrooms. Therefore, if we want safe drinking water to be available in schools and daycares, adequate provincial funding must be provided to fix the root causes of lead in drinking water.

Fix Our Schools has been asking the provincial government to develop & implement a standard of good repair for our schools. So far, our call to action has been ignored. School conditions matter. They impact student learning, attendance, and health. #onted #onpoli #OntarioBuilds pic.twitter.com/79MJNRh3w5

— Fix Our Schools (@Fix_Our_Schools) February 20, 2020

The Province must develop and fund a Standard of Good Repair for Ontario’s schools. There is currently no standard of good repair for Ontario’s schools that would outline the metrics that could be used to measure whether a school is, indeed, in an acceptable state for children to spend their days. While our provincial government has been diligent in collecting disrepair data in schools, this data does not reflect lead in drinking water, asbestos issues, rodents and vermin, classroom temperatures, indoor air quality, nor is disrepair tracked and reported on any portables.

While the above solutions focus on what Ontario’s provincial government must do to ensure safe drinking water in provincial schools and daycares, we must also address safe drinking water for Canada’s Indigenous Peoples, including access to safe drinking water in schools. A May 6, 2021 article in TheTyee.ca entitled, “My Community’s Boil Water Advisory Is Almost as Old as Me“, author Valerie Ooshag starts by reflecting on her remote fly-in community of Eabametoong First Nation, which has been on a boil water advisory since August 2001. Ooshag also takes a broader look to note that there were 52 long-term advisories in effect as of April 2021, impacting 33 communities. This unacceptable situation continues to exist despite a 2015 commitment by Prime Minister Trudeau to lift all boil-water advisories by 2020.

Ooshag states, “Canada is a first world country, with Indigenous populations and communities having to live under boil water advisories, with some children and youth never having had access to clean drinking water in their entire lives. In the 2015 election campaign, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau vowed to lift all boil-water advisories by 2020. It is now 2021, and yet there are still these 52 advisories affecting 33 communities that don’t have access to clean drinking water.”

Inconceivably, there is no new target date for the government to keep its six-year-old promise. We recently gave Canada and Premier Ford a failing grade and continue to do so in relation to the issue of safe drinking water for all citizens. Both Canada’s federal government and Ontario’s provincial government can and must do better on this issue.