First, a message to Premier Ford and Education Minister Lecce:

A trial balloon is defined as “information sent out to the media in order to observe the reaction of an audience. It can be used by politicians who deliberately leak information on a policy change under consideration.” Premier Ford and Minister Lecce (wherever you may be amidst this crisis in public education) – is this a trial balloon or a formal announcement that Ontario’s children will return to school in-person on January 17?

If it is the latter – a formal announcement – then we look forward to a press conference very soon where you both provide a detailed explanation of what has been done/will be done to ensure that schools are in a safer and healthier position than they would have been had our children returned to school, as planned, last Monday, January 3. This announcement would include numbers and data that give us a level of confidence that your government has been tracking key indicators (community spread, reproduction rate, vaccination rates, hospitalization rates, hospital and ICU capacity, and the possible list goes on). This announcement would demonstrate how positive changes in these key indicators actually address the primary concerns that led you to announce the latest pivot to online learning – namely hospital system capacity and teacher “absenteeism“.

Ontarians deserve to understand how you are making decisions about our children’s lives and education. Transparency is necessary for any democracy to work effectively and efficiently, and Ontarians are looking through a frosted glass window covered with mud at this point. At various times during the pandemic, the Ford government seems to have relied on the Science Table, SickKids, local public health units, small businesses, large businesses, and popular opinion to inform decisions about Ontario’s children, schools and education. So, if this is, indeed, an announcement – we look forward to a transparent explanation.

If it is the former – a trial balloon – then shame on you for behaving in the most disrespectful of ways to Ontario’s children, parents, families, teachers, education workers, and employers. Anxiety, confusion, fear – these are the emotions your government perpetuates among its citizens by throwing out trial balloons. Ontarians deserve and need leadership – not to be a part of some marketing or polling exercise for the provincial election in June.

Fix Our Schools wrote the following blog just prior to the news being released that Ontario’s children would be returning to in-person learning on January 17. The facts below remain so we are publishing this blog today, regardless of the latest news. Should this news end up being the trial balloon that we suspect that it is, we are guessing we will receive an actual formal announcement in about four days.

And now, the blog, as written prior to the news that Ontario’s schools will reopen January 17 (notice how the facts remain the same?)

Ontario’s students are now in their 28th week of online learning since the COVID-19 pandemic began almost two years ago. Ontario children have missed the most in-person school days of any jurisdiction in North America, despite the fact that our premier has disingenuously stated time and again throughout the pandemic that Ontario schools would be “first to open and last to close”.

This latest pivot to online learning was announced last Monday – the day that Ontario students were meant to be starting back to school after winter holidays – and has enraged Ontarians.

In a January 7, 2002 article in the Star entitled, “It’s disrespect”, says Toronto school advocate of latest school closures, Fix Our Schools supported People for Education’s calls to: resume school COVID case reporting; add COVID-19 vaccinations to list of mandatory vaccines to attend school; provide N95 masks to all educators and students and secure sufficient rapid tests; audit classroom HEPA filters; provide boards promised funding to enable smaller classes and physical distancing; and convene a COVID education advisory task force with health and education representatives.

Fix Our Schools also linked school closures to our economy. “Productivity in our economy is very much linked to schools and education. Somehow, that seems to be lost on the Ford government,” states Krista Wylie, co-founder of Fix Our Schools. She goes on to say that, “The Ford government time and again seem to view money spent on education as an expense rather than the investment that it is.”

In the same Star article, ETFO’s president Karen Jordan stated that “this shift to remote learning is frustrating because we know it could have been avoided had the province funded and implemented safety measures at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and not half-measures.” And OECTA president Barb Dobrowolski said that this latest Ford government decision was “yet another reactionary measure in a long list that stems from this government’s abdication of leadership, which has repeatedly failed students, parents, teachers, education workers, and all Ontarians.”

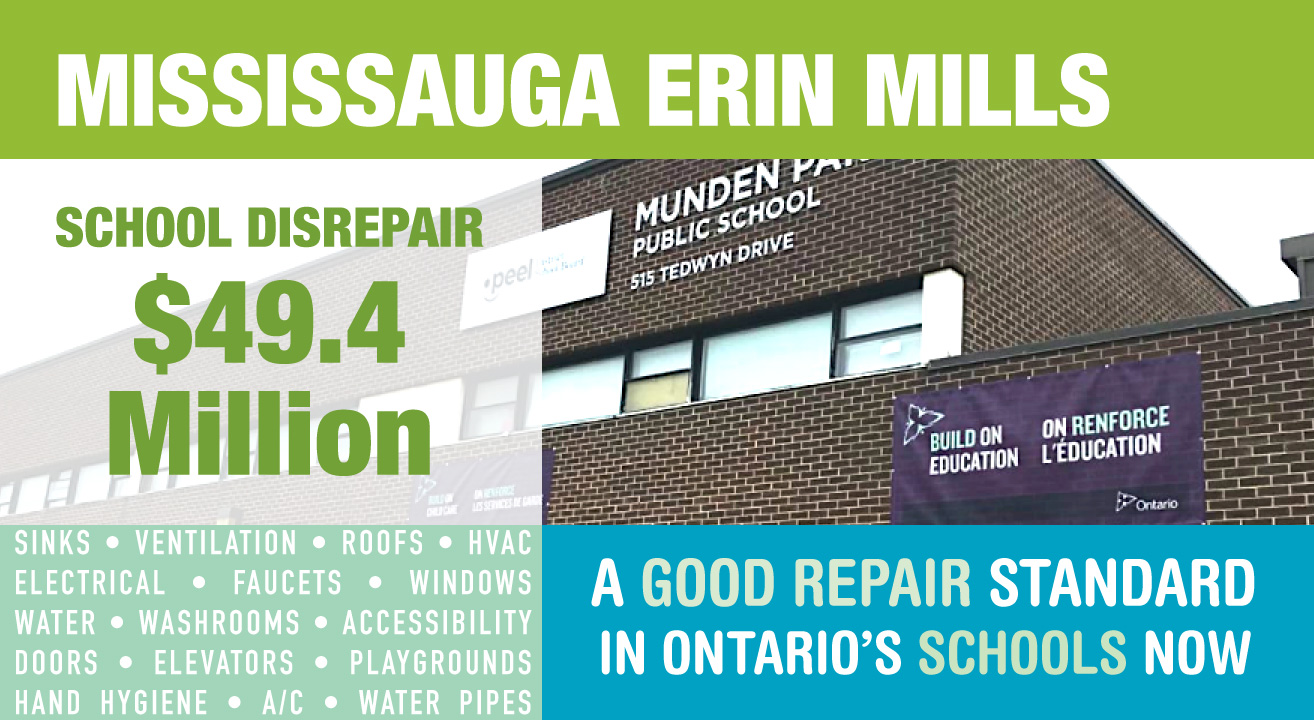

Shawn Micallef adds to the discussion in his excellent opinion piece from January 8, 2022 entitled, “Doug Ford isn’t the first premier to drop the ball on making schools safe. Omicron highlight’s a decades-old problem”. He validates the current frustration among Ontarians by acknowledging that, “we’re coming up on two years of this pandemic and two years of the Ford government telling us everything is being done to make schools safe. We were told that during the break last summer, and the pandemic summer before that. And now we’re told two more weeks should be enough. How many times can they say this?” He then reflects how successive provincial governments of different political stripes have allowed Ontario’s publicly funded schools to deteriorate. “Inadequate and not-yet-upgraded HVAC systems, crowded classrooms and the poor state of repair have been endemic to Ontario’s school system. Public schools are one of our civic backbones and so many of them were built solidly, to last, as a statement that they and what they represent matter. All buildings age and need repairs and renovations to keep up with current standards of accessibility and safety. Ventilation upgrades, especially with climate change (pandemic notwithstanding) are a critical part of this.”

Fix Our Schools echoes Micallef’s sentiments and agrees that current the state of Ontario’s schools is the result of over two decades of provincial governments failing to prioritize schools as critical infrastructure. As we stated back in August, 2020, when we wrote the blog entitled, “Our Provincial Government Cannot Continue to Rely on Miracles“, “it isn’t realistic to starve a system for over two decades and then expect that it is in tip-top shape for you in a pandemic.” Let this be a lesson for all provincial parties that schools are critical infrastructure. Full stop. Regardless of whether Ontario’s governing party is right-leaning or left-leaning, Ontario schools must be adequately funded to ensure they are safe, healthy, well-maintained places that provide environments conducive to learning and working – even amidst a pandemic. Had children, schools, and education been prioritized throughout the pandemic, much more in-person learning could have been possible.

Dr. Picard’s January 9 opinion piece in the Globe & Mail entitled, “Of course schools should remain open. It’s the “how” that matters” aligned with this sentiment. He started by acknowledging that the debate over whether schools should be open or closed is “one of the most fiercely debated questions across Canada and around the world as we enter year three of the pandemic.” However, Picard then suggested that this was actually the wrong question, stating that “Of course schools should remain open. At the very least, they should be the last thing to close, because they are as essential as grocery stores and hospitals. Children need to learn, to socialize, to play, for the sake of their development, and their physical and mental health. Their parents need to work. How dare we tolerate school closings while still allowing in-person dining, nail salon manicures, professional sporting events and so much more? (Depending on the province, of course.) We need to get our priorities straight.” Instead, he recommended that we should be asking ourselves, “How can we best protect children from the ravages of the pandemic? Trying to prevent children from being infected is important, even if they do appear to have less severe outcomes. So too is protecting kids from collateral damage, like the mental health effects of isolation.”

New Hamburg mother Shannon Syder echoed Dr. Picard’s concern over the negative mental health impacts of school closures in the Toronto Star piece of January 9, 2022 entitled, “Is it up to our kids to sacrifice their education and mental health to save our hospitals?” Snyder wonders, “if everyone can agree on something, it should be that we should be prioritizing our kids and their education and their mental health. For me it comes down to this — is it up to our kids to sacrifice their education and mental health to save our hospitals? That just doesn’t make sense to me, and I think we need to have a real conversation about what these long-term effects are going to be if we stay on this path.”

However, perhaps this one letter from an Ontario parent to Premier Ford and Minister Lecce that we were copied on this past week says it best:

“I want you to know that ALL parents are talking about this week is how your government has completely failed us and our children. This wave has exposed your shortcomings, all the things that you said you were going to do to make schools safe, but that you haven’t fully followed through on.

My question is this – what are you doing RIGHT NOW to improve the safety at schools so that our kids can return on January 17? Testing plan, vaccination plan, masks, ventilation, etc. etc. I cannot believe that my kids can go to the mall but cannot go to school right now. You are making our children bear the brunt of this pandemic, so that you can keep your business constituents happy.

You said that schools would be the first to open, and the last to close, and you have failed on that promise. You will not get re-elected if you do not SAFELY open schools in a couple of weeks. Your time is up… Please take concrete actions today to make the schools safer to that they can re-open.”

Fix Our Schools has been urging the Ford government to prioritize safe, in-person learning for Ontario children amidst the COVID-19 pandemic since Spring of 2020, and we are not alone. The Ontario Science Table’s briefing from back in July, 2021 entitled, “School Operation for the 2021- 2022 Academic Year in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic” emphasized that education was “children’s essential work”, that schools are of critical importance to students’ learning and overall well-being, and that in-person schooling is optimal for the vast majority of students. Amy Greer, an infectious disease epidemiologist and math modeller, was one of the co-authors of this report and reminds us this week that this detailed plan existed back in July, 2021, and was ignored by Premier Ford and Minister Lecce. As a result of the Ford government’s “back to school plan”, which really simply relied on low community spread, Ontario’s children, families, employers, teachers, and education workers are all paying a high price now as we face another round of online learning.

Students, families, employers, teachers and education workers are all eager to know what exactly is being done to ensure a safe return to in-person learning as quickly as possible. We are also eager to understand what exactly needs to be in place for the Ford government to decide that children may safely return to school in-person? What indicators are being tracked that will tell us that in-person learning can safely resume? Premier Ford and Minister Lecce – over to you!

We know that you did not sign the Fix Our Schools Pledge during the 2018 election. However, as we head into another provincial election in June 2022, we trust that safe, healthy, well-maintained school buildings will be a priority for all parties.

We know that you did not sign the Fix Our Schools Pledge during the 2018 election. However, as we head into another provincial election in June 2022, we trust that safe, healthy, well-maintained school buildings will be a priority for all parties.